We have moved….

Posted: November 7, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentIt has been quite some time since I updated this blog – partly because life just gets in the way but partly because I was finding the focus on Photoshop a bit too limiting.

While I am still passionate about teaching scientists how to create fantastic images with Photoshop, I really wanted to broaden my scope to include other types of image manipulation software (such as ImageJ and GIMP) as well as other practical advice on making life in science easier.

So a little while ago I started a new blog called Come Science With Me. The goal of Come Science With Me is to “Help scientists do science”. It aims to cover those skills that we all seem to need but never actually get taught. I’ve been dabbling with the blog for a while and now I’m launching it with a full year’s plan of monthly focus areas (this month, November, we are all about graphic design).

So please, if you have liked this blog in the past, come over and join us. And if you are a current subscriber to Photoshop for Scientists, please consider subscribing to Come Science With Me.

A little bit about me!

Posted: July 17, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized 2 CommentsToday I thought I would tell you a bit about me, my career in science so far and the reasons why I started this blog.

My name is Jo-Maree Courtney – I’m never quite sure how to describe myself beyond “Scientist”. I started out in Neuroscience, did my PhD in Developmental Biology and am now doing a post-doc in Respiratory Medicine – but what all these areas have in common is Molecular Biology and that is my first and continuing fascination.

I clearly remember the high school science unit when we learnt about Mendelian genetics and the basics of meiosis, mitosis and DNA replication. Something in my head just clicked and I knew that’s what I wanted to do. (At around the same time I was reading Jurassic Park – before the film was made – and that just excited me about the potential of DNA even more!). Throughout my undergraduate career at the University of Tasmania I continually made whichever choices gave me the most opportunity to learn about genetics and molecular biology. This resulted in studying quite a bit of botany as the botany department at UTAS specialised in genetics – and left me with a lifelong love of Tasmanian native plants and the ability to identify several species of eucalypt by smell alone! However I was always more interested in genetics as it related to human disease so for my honours research project I moved into neuroscience and studied the potential for regeneration of injured spinal cord neurons.

After graduation I moved from Tasmania to London with my English fiancé (now husband) and, after a bit of time spent in temporary work to fulfil visa requirements, got a position as a Research Technician at University College London in a group studying calcium channels, particularly related to epilepsy. During this time I got my first real experience of using Photoshop – mostly with immunoflourescence staining – and I was hooked.

With two valuable years of lab experience under my belt I began to look around for an inspiring PhD project and eventually found one at King’s College London studying tooth development. I continued to develop my Photoshop skills and soon found that my colleagues and fellow students were coming to me for advice. By the time I completed my PhD and embarked on post-doctoral research in the same department, I was running regular Photoshop for Scientists tutorials.

The next few years were punctuated by breaks for maternity leave when my two sons were born and a hiatus from academic research while I took up a technical position that better enabled me to concentrate on my growing family. However I continued my interest in Photoshop and continued to run tutorials for the students and post-docs in the department.

Finally, last year I left London and returned back home to my native Tasmania, with my husband and two small boys, ready to continue my academic career. I am now back where I started at the University of Tasmania but now I’m applying my experience in molecular and cellular biology to the field of respiratory medicine.

So that’s me! I’d love to hear about you – what field of science do you work in? Are you an undergraduate, PhD student, post-doc? How do you use Photoshop in your work?

What size should my image be?

Posted: July 3, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentOne question I get asked a lot by colleagues and students is how big should their image be?

There are two related sides to this question – the first is resolution and the second is actual size. I will discuss resolution in more detail in later posts but as a rule of thumb you should have a resolution of at least 300dpi for print or publication. If the image will only ever be used in a presentation you can (and should) take the resolution down to 75dpi.

With regard to the actual size – it depends on the destination of the image. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the image for a publication? In this case, look at the dimensions of the journal in question. Do you want your image to fill a whole page or just one column? You may not have the final say in the positioning of images in your paper but you can plan whether to create wide or narrow images to help with an appealing layout.

- Is the image for printing in a thesis or dissertation? In this case you will likely have your image on a page of its own with a caption. I suggest you make the image approximately half the size of the whole page. If you will be printing on A4 paper, making your image A5 size (148mm x 210mm) is a good start. An A5 page, in portrait orientation, fits beautifully on an A4 portrait page leaving plenty of room for margins, binding and a caption. Much bigger and your page will look crowded, much smaller and your image will look insignificant in the middle of all that white space.

- Is your image for a presentation? Take a look at your slide layout – do you want the image to fill the page or just a portion of it? Set the appropriate dimensions before you start creating your image.

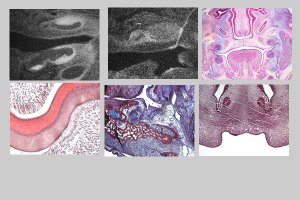

The other thing to take into consideration is the dimensions of your original data image (if you are compiling a montage like the one shown here). You will need to think about how many rows and columns you need, whether you need room for labels, and whether the images are to be used as is or cropped.

Whatever you decide to do it is always worth thinking about these things before starting to put together your figure – it is much easier than changing things around later.

Have you discovered any useful rules of thumb for sizing images?

Creating images for publication in Nature

Posted: June 28, 2012 Filed under: Ethics 1 CommentWe all aspire to be published in Nature – but how many of us have actually read the policies set out by the Nature Group, particularly those relating to image integrity?

Most (if not all) journals have policies and guidelines on image integrity and it is worth becoming familiar with there before you do your experiments or acquire your images. Some of the policies refer to image acquisition practices, others require you to keep records of equipment settings – it is not always easy or even possible to do this retrospectively once to get close to submitting a manuscript.

I suggest you go and take a look at the Nature policies (most other journals will be similar) but in the meantime, here are some highlights:

“Authors should retain their unprocessed data and metadata files, as editors may request them to aid in manuscript evaluation.”

I can’t even begin to count the number of times a student or colleague has come to me asking for help with an image but has been unable to locate their original files. If they can’t find them for me then how will they find them when Nature’s editors request them? It is vitally important that you keep your original image files untouched (directly as they come from your acquisition software) and in a logical filing system so that you can find them, possibly years later, if required. There are any number of ways to achieve this and I’ll be investigating some of them in a later post but the most important thing is to develop a system and stick to it!

“All digitized images submitted with the final revision of the manuscript must be of high quality and have resolutions of at least 300 d.p.i. for colour, 600 d.p.i. for greyscale and 1,200 d.p.i. for line art.”

At least 300 dpi for colour images and even greater for grey-scale and line art! This is one that I have seen people get caught out by many times. It doesn’t matter how good your image is, if you have prepared it at a resolution of less than 300 dpi then it won’t be accepted. And if you can’t find your original files to redo the image (see above) then you are stuck. My advice is always work at the highest size and resolution your computing power will handle. Remember, you can always reduce the size and/or resolution of an image but it is impossible to increase resolution once it has been lost.

“Manuscripts should include a single Supplementary Methods file (or be part of a larger Methods section) labelled ‘equipment and settings’ that describes for each figure the pertinent instrument settings, acquisition conditions and processing changes, as described in this guide.”

Could you tell me the exact settings on the microscope for the images that you took yesterday? Do you know the exact degree to which you adjusted the contrast on your images last week? If the answer is no, then you are going to have trouble writing the required Supplementary Methods file. Before you dive in and start taking pictures, make sure you fully understand the workings of your equipment. Take a note of all settings (even those you don’t change as you never know if another user may change them between your sessions) and make sure you keep them consistent. Use your lab book to note the instrument settings each time you use it and make a note of things like exposure and gain for each image acquired. Some acquisition software will record this information for you and store it in the Exif data – if you rely on this then you will need to ensure that your original files are maintained with this data intact.

“The use of touch-up tools, such as cloning and healing tools in Photoshop, or any feature that deliberately obscures manipulations, is to be avoided.”

This one is a bit of a no-brainer to me but I have often been surprised by the number of researchers who think it is okay to use the touch-up tools as long as they aren’t changing the data. As far as I am concerned these tools should never be used on scientific images (well, almost never – there are some very specific cases where they may be useful but their use must always be very carefully considered). Unless you really know what you are doing and why you are doing it, steer clear of the touch-up tools.

“Processing (such as changing brightness and contrast) is appropriate only when it is applied equally across the entire image and is applied equally to controls.”

In an ideal world there would never be any need for post-processing scientific images. Your microscope and/or camera should be set to take perfect images in the first place. While this is the aim, it is not always possible to achieve so it is accepted that some level of post-processing is allowable. However you should always make sure that you process all your images (both experimental and controls) in exactly the same way. If you have a lot of images the best way to do this is by using Photoshop’s batch processing tool to apply the same manipulation to multiple images at a time.

I will be discussing this topic further in future posts but for now I have some questions for you:

- Have you ever taken the time to read journal’s image integrity policy before?

- Do you have a logical filing system that works – or one that doesn’t?

- Have you ever been caught out when trying to publish your work?

What do YOU need from this blog?

Posted: June 27, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentToday I’m asking you to get involved. I have lots of ideas about what this blog and associated courses should cover but I’d like to hear from you. This website gets a good number of hits from such search terms as “create scientific figures photoshop” and “photoshop as a scientific tool” but I would like to hear specifically what you are looking for.

Please drop me a message if:

- you have a specific problem using Photoshop for a scientific application that you would like me to address;

- you would like to have your work using Photoshop featured on the blog as a case study;

- you have some good examples of either good or bad use of Photoshop for scientific images

Rest assured that any work featured here can be anonymous and specific details of experiments etc will not be revealed so you need not worry about your unpublished work getting out there ahead of time!

I’d really, really like to hear from scientists outside the molecular and cell biology fields (where my experience lies).

I am working on developing a series of e-books/courses covering various aspects of Photoshop for Scientists. I would love to hear what you think and whether you think I should cover anything in particular. This is what I have planned at the moment.

- The Five Golden Rules of Photoshop for Scientists – this will be a free e-book discussing sure important topics as resolution, image integrity, and file management.

- Introduction to Photoshop for Scientists – this ebook or ecourse (I’m not sure which yet) will be available for a small charge and will take you through the basic tools in Photoshop required to construct accurate, consistent and appealing montages without spending hours each time!

- Colour manipulation in Photoshop for Scientists – another ebook/course which will look at the various ways you might want to manipulate the colour (hue, brightness, channels) in Photoshop and delve into the thorny issue of exactly what constitutes an acceptable manipulation and what would be considered falsifying data.

- Drawing scientific diagrams in Photoshop – my third ebook will look at the various ways you can use Photoshop to create beautiful and informative diagrams to illustrate your research.

Please let me know your thoughts on the above!

5 Sites for Photoshop Tutorials

Posted: June 25, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentAlthough they rarely cover topics directly relevant to scientists, tutorial sites are a great way to learn the various features of Photoshop. Even though you think a particular tutorial may have no relevance to you, you never know when a technique or tool might come in useful. If you look for the short tutorials that only take a few minutes you can quickly learn new skills that you may later find a use for. And if not, then they are just good fun!

I used this site a lot when learning Photoshop and I still dip in every now and again. It has a lot of nice, quick tutorials so you can do one if you just have a spare 5 minutes to fill in. I especially like the ones in the Special Effects category such as this Artistic Abstract Shape as they get me playing with parts of Photoshop that I wouldn’t otherwise think to try.

Among all the brush, shape and action downloads (which are another whole topic) there are some lovely tutorials on the official Adobe site.

I admit I haven’t been on this site for a while but I used to use it regularly. Looks like it still lives up to its name!

This site has a nice selection of good looking tutorials. I especially like this one: Colin’s 10 Principles for Better Type Design – lots of very sound typographic principles to apply to your posters and presentations.

While there is plenty to learn about Photoshop from Smashing Magazine, I want to particularly draw your attention to this post compiling some of the best tutorials to be found on the web. So many interesting things here – I think I could get lost for hours!

Of course, there are plenty more Photoshop tutorial sites out there – search Google and see what you find. Next time I’ll give you an example of how following a random tutorial about using paintbrushes led to me solving a question that had bugged me and my colleagues for years!

So now it’s over to you. Your challenge for the weekend is to follow a tutorial or two and let me know how you get on. Let me know which ones you like and find useful.

Photoshop CS6 – what does it have for scientists?

Posted: June 18, 2012 Filed under: Photoshop - general | Tags: Adobe, Photoshop 3 CommentsSo Adobe has recently released Photoshop CS6. I’ve only recently installed CS5 on my home computer so haven’t really had a chance to get used to that yet but I should be getting CS6 on my work computer towards the end of the month. There has been a lot of buzz in the graphic design world about the updates but as far as I can see so far, few of the changes will be relevant to scientific imaging (being mostly to do with the content-aware tool and other image manipulations that are not relevant to scientific images). There are a few changes I’m looking forward to testing out though:

The new user interface.

Apparently Adobe has modified the user interface to make it easier to keep track of multiple documents and panels. I haven’t quite got used to the CS4/5 interface yet but am looking forward to seeing what CS6 can do as I often have multiple documents open at the same time.

The ability to stroke a path with a dotted line

This is an exciting new feature for me as I very often use a dotted line over an image to highlight a particular region of interest. It really bugged me during my PhD that I couldn’t work out how to do a proper dashed line (as opposed to dots) and I finally figured it out a few weeks after submitting my thesis! Looks like this new feature will make it much easier though. For those who aren’t upgrading to CS6 I’ll do a tutorial about how to do a dashed line in earlier versions soon.

Background saving

This sounds interesting. When making montages with lots of layers it is important to save regularly but large psd files can take a long time to save and it can be frustrating to have to wait. Now we should be able to continue editing other images while saving large files. Yay!

Creative Cloud

I don’t think I’ll be subscribing to the Creative Cloud as with educational pricing it’s going to be better to just buy the software outright, but if I were looking to purchase the software for home use and having to pay full price then I think I would consider the subscription type service.

Of course, I’m also looking forward to playing with the image manipulation tools as I love to use Photoshop for design and photo manipulation as well as scientific imaging. And you never know when a tool designed for creative purposes may come in useful for technical imaging.

Are you going to upgrade to CS6 soon? Are you interested in the Creative Cloud idea? And have you ever found a use for the Content Aware tool and other image manipulations within scientific imaging? I’d love to hear from you!

10 tips for using rulers and guides in Photoshop

Posted: June 14, 2012 Filed under: Tips & Tricks | Tags: Photoshop, Ruler 9 CommentsRulers and guides are an often overlooked feature of Photoshop – there isn’t that much use for them when editing photos or creating original artwork but for scientific images they are invaluable. Today I’m going to offer you a series of tips to get the most out of these tools and have your images looking professional and neat.

But before we start – what are guides and why should you use them? Guides are non-printing lines that can be placed vertically and horizontally on your canvas to help you line up the various objects or items on the page. How many times have you been to a presentation and seen a montage of images which weren’t properly lined up and with uneven spacing between them – like this?

It looks messy and unprofessional and gives an impression of sloppiness that you definitely don’t want associated with your work! Setting up a simple series of guides will allow you to accurately place your images so this doesn’t happen.

1. Set guides accurately using New Guide

When you know exactly where you want to place a guide, use the New Guide option under the View Menu. You can choose to set a horizontal or vertical guide and enter the exact position you want it to be. You can use whatever units you want here – pixels, centimetres, inches – just type is after the figure, eg: 450 px, 4 cm or 3 in (note: you can type inches or in but not “)

2. Set the snapping options

Turning on snapping means that your objects will snap to your guides (that is, when you get close your object will jump to align with the guide and you don’t have to do it by eye). Check that Snap is ticked in the View Menu. Underneath Snap you can select exactly what you want things to snap to – guides, layers etc. It’s usually best to leave these all turned on but there may be time when you want to uncheck one of more of them. For example, if you have a guide very close to a layer edge, Photoshop might have a hard time knowing which of the two you want to snap to.

3. Pull out guides and snap to existing objects

Once you have snapping turned on (and set for Layers) you can use it to pull out guides to fit an existing object (assuming the object is on its own layer). Start by placing one image on your page and make sure the rulers are visible (View – Rulers). Also make sure that the layer you want to snap to is active. Now click in the top ruler and drag downwards to pull out a guide. When you get close to the top edge of your object the guide will snap to the edge and you can release the mouse button. Now you can snap other objects (each on their own layer) to this guide and they will all be perfectly aligned. Do the same for a vertical guide by pulling out from the side ruler.

4. Reposition or delete a guide

To reposition a guide, activate the Move tool and hover your cursor over the guide. Your cursor will change to a pair of parallel lines with arrows. You can now pick up your guide and move it. If you want to remove a guide simply drag it back to the ruler. You can remove all guides by choosing Clear Guides from the View Menu.

5. Lock guides to avoid accidentally changing them

Once you have your guides set up you can lock them (View – Lock Guides) to prevent them being moved or deleted accidentally. Now they can’t be moved or deleted but they can still be cleared or hidden.

6. Divide your canvas using guides set as percentages

Often it is useful to divide your canvas up into equal sections and it’s easier to do this by percentage than working out exactly what one quarter of your page size is. If you have snapping set to Document Bounds then you can drag out a guide and it will snap to the exact centre of the canvas (or the edges) but what if you want to dive your page into 4 or 5 equal sections? Simply go to View – New Guide and enter a position as a percentage. Try setting vertical guides at 25%, 50% and 75% to divide your canvas into four equal columns.

7. Change the units of the rulers to best suit your purpose

Sometimes it’s useful the change the units of measurement on your rulers. You can set them to pixels, centimeters, inches, percentages, millimeters, points or picas. To choose the appropriate setting go to the Edit Menu and select Preferences – Units and Rulers.

8. Move the zero point of the rulers

By default the zero point of the rulers is the top left corner of your canvas but sometimes it is useful to move this point, often to the centre of the canvas but sometime to another point (perhaps the top left corner of a particular layer). Do this by clicking in the small white square in the top left corner where the two rulers meet. Drag out the pair of thin black lines. If you already have guides or a layer set in place they will snap to it (assuming you have the snapping options turned on) and they will turn red when they are over a guide. When you let go the zero points of the rulers will change to this location.

9. Change the colour of the guides

If the default cyan colour of the guides is difficult to see on your particular document you can change the colour in the Guides, Grid & Slices section of the Preferences window (Edit – Preferences). You can select one of the standard options or choose Custom to select any specific colour you want. You can also choose to have dashed lines instead of whole ones.

10. Show and hide guides

Sometimes the guides can become distracting so you can temporarily hide them by unchecking Extras in the View menu (to hide all extras) or Guides under View-Show (to hide the guides but keep paths and grids etc visible).

I hope some of these tips have been useful to you. If so please let me know in the comments below and also please leave a comment if you have any questions or suggestions for future posts!

Photoshop vs PowerPoint

Posted: March 29, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized 2 CommentsFirstly I would like welcome my new subscribers – I have noticed quite a few of you have signed up and it’s wonderful that there is such interest in this topic out there!

I apologise for the lack of progress in getting things up and running here but a number of things have gotten in the way (such as starting a new job). Rest assured I haven’t forgotten you and I am planning to get things going within the next few weeks.

Anyway, on to today’s topic. I was asked by my new boss to help a colleague with a diagram that needed ‘prettying up’ for a presentation next week. Of course I said yes (especially as it would make a nice change from reading journal articles which I’ve been doing for the past two weeks). But when my colleague said he had prepared it in PowerPoint my heart sank. I don’t yet have Photoshop installed on my new work computer so I had no choice but to do the best I could in PowerPoint.

Now, I understand why PowerPoint is often used by researchers to make diagrams for their presentations, and even for publications. It is familiar, accessible and doesn’t have a steep learning curve. And it tends to just be there – installed on every computer alongside Word and Excel. But the diagrams created with PowerPoint usually leave a lot to be desired, especially if the user doesn’t really know how to make the best use of the program’s features.

So I have always advised students that PowerPoint is for presentations and Photoshop or Illustrator should be used for diagrams.

However, having been forced into using PowerPoint today I discovered at it has a lot of new features that I hadn’t explored before and I was actually able to make a diagram that I was really pleased with. By carefully using lines, gradients, accurate size and position and the alignment tools I was able to greatly improve upon the original image. But what got me really excited with the ability to draw with bezier curves! I had no idea PowerPoint had this feature and, while it’s not quite the Pen tool, it opened up a whole new world of possibilities. Suddenly I wasn’t limited to the available standard shapes but could draw my own cells any way I wanted.

So maybe Powerpoint isn’t all bad when it comes to making diagrams. I would still prefer to use Photoshop any day of the week but when needs must, I guess Powerpoint has some potential too.

Do any of you use Powerpoint for drawing diagrams? Have you experimented with Bezier curves?

Welcome!

Posted: January 16, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized 5 CommentsHello and Welcome!

My name is Jo-Maree Courtney. I’m a scientist with a PhD in Developmental Biology. I love Photoshop and I’m interested in the principles of design, especially when applied to scientific imaging.

Photoshop has become an essential tool for scientists who use it to take raw image data from their microscopes, cameras and other sources and present them in a way that makes their results understandable. I love learning about Photoshop and during the course of my PhD spent a lot of time learning the tricks and tips that would allow me to produce consistent and visually appealing images with minimum of time and while maintaining scientific integrity. However I soon realised that not all my fellow students shared my enthusiasm for the software. In fact I seemed to be in a minority of one.

Once the other students and researchers in the department realised I knew my way around Photoshop they started coming to me for advice. Informal advice sessions soon turned into organised tutorials which developed into a series of regular courses. Now this blog is a way of taking my courses to a wider audience.

If you work in research science – whether as a technician, graduate student, post-doc or senior researcher – I hope you will find something useful here.

Over the coming months I will be building up a number of courses covering different aspects of using Adobe Photoshop for scientific imaging. I will also discuss the issues that need to be considered to maintain integrity of your data and optimising your time while creating visually appealing and professional images.

If you ever have any specific requests or problems please feel free to leave a comment. I look forward to hearing from you!